Stubborn Abstractions: Don Sorenson’s Eye Dazzlers

Although rarely alluded to in today’s amnesiac art world, Los Angeles artist Don Sorenson’s zigzag paintings from the late 1970s just won’t go away. With their dense surfaces and limitless sense of space, they create visual aftereffects that literally linger in the eye. Moreover, given attention, each of his paintings gradually resolves into a discreet system with a kind of “thingness” that lodges in the mind.

Sorenson’s career, tragically cut off by his premature death at the age of thirty-seven, was packed with experimental twists and turns, stemming from the solid zigzag works first shown in 1975 at Nicholas Wilder Gallery. These rigorous compositions are in the vastly under-recognized tradition of West Coast abstraction by artists such as Oskar Fischinger, Peter Krasnow, John McLaughlin, Lorser Feitelson, Karl Benjamin, and June Harwood. They also relate in fascinating ways to the challenging contemporary west-coast abstractions of Ed Moses, Robert Irwin, Joe Goode, Ron Davis, Gary Lang, and John M. Miller.

Operating largely out of step with the conceptually ironic, formally loose artwork of the 1970s, Sorenson’s paintings confronted formal issues that have remained at the heart of serious abstraction. The spatial illusions of his works were born from an impulse to transcend the stultifying limitations decreed by the pundits of High Modernism and Minimalism. Seeking a more actively engaged viewing experience, he gleefully violated critic Clement Greenberg’s notion that paintings should acknowledge the inherent flatness of a picture plane. Art historian Melinda Wortz cites Sorenson’s interest in the spiritually inflected ideas about abstraction of Kandinsky, Malevich, Mondrian, and Agnes Martin.

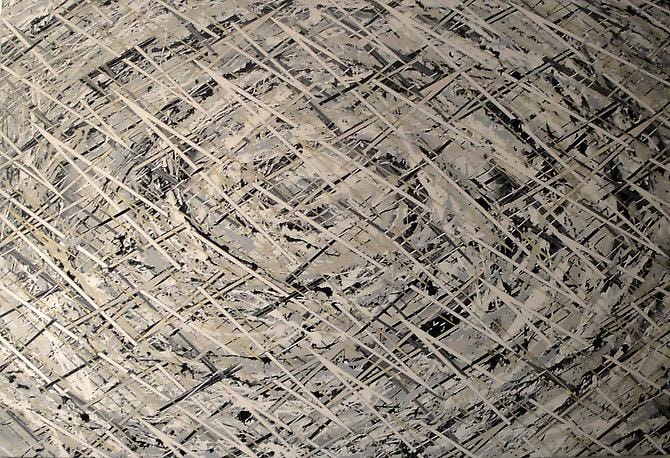

The zigzag motive provided a means to toy with the grid structure so prevalent in geometric abstraction. Experimenting with overlapping, juxtaposing, and interwoven lines, Sorenson created spaces that are illusionistic yet decidedly not perspectival. The paintings’ dense, disorienting fields depict nothing but vectors in a strangely unsettling, all-over deep space. These works manage to dissolve the traditional tussle in painting between figure and ground. By not representing or delineating a specific space, they assume a role as fully-fleshed abstract objects – thus achieving a kind of “pure” abstraction similar to that desired by Malevich and Mondrian.

In some of the paintings at the end of the decade, Sorenson began weaving meandering gestural lines into the crisp, zigzag structures. The loose squiggles of paint seem to exist somewhere inside a tight geometric grid – a place without a ground that lingers as a solely intellectual construct. This “pure” abstract space melds gesture and line, as well as the primary colors, off-kilter pastels and decorator hues that Sorenson chooses to juxtapose and overlap. In the visual stews of later paintings, he began to embed shapes, silhouettes, and washes of color within the zigzag grids, encasing lines, gestures, and images like flies in wildly crisscrossed amber.

Like Minimalist sculptures and paintings, Sorenson’s works engage the viewer in a kind of interactive theatrical experience, one based on perception. In an interview with critic Colin Gardner, Sorenson summarized the intentions of his early work: “I was very interested in perception and how we see, how we make a gestalt, the whole idea of the figure in a ground. At the time I was reading a lot of Merleau-Ponty and his ideas on creating your own reality, that there’s a very important connection between the subject and object. (There’s a tension there because neither of them can exist without the other.) Applying that understanding to painting, the spectator is really making the painting, and vice versa. I was intrigued with the idea of creating a new structure beyond minimalism.”

With its implication of oblique motion, the zigzag motive enabled Sorenson to create dense structures of vectors that viewers can slowly untangle over time. He was undoubtedly aware of the zigzag patterns featured in the traditional “eye dazzler” and “wedge weave” designs of the Navahos, developed in the nineteenth century. Impressive examples of these designs were presented in the Los Angeles County Museum of Art exhibition, “The Navaho Blanket,” curated by Mary Hunt Kahlenberg and artist Tony Berlant, and opening in 1972 while Sorenson was still in the MFA program at Cal State Northridge. Rooted in their traditions, the Navahos cherished their woven blankets as clothing, thinking of them as a way to “walk in beauty.” This organic connection to the visually charged patterns imbued the blankets with spiritually organic, life-enhancing meaning.

Like the “eye dazzler” blankets, Sorenson’s paintings seem to invite viewers to try them on, to decipher their dense of fields of marks and vectors. To do so is to engage in a special kind of beauty, one stimulated by the intellect. Melinda Wortz cites Sorenson’s involvement at the time in Zen meditation and Buddhist philosophy’s advocacy of “the unification of opposites which lies beyond dualistic thinking.”

Ed Moses’ contemporaneous grid paintings of the 1970s and 80s similarly drew on Navaho abstract motifs to create dense, unmoored fields of abstract space. In these works, the critic John Yau saw a psycho-sexual resolution of opposites that might apply also to the gesture-embedded grids of Don Sorenson:

With their densely layered diagonal grids evoking a vertiginous, open-ended space, the viewer might conclude that the artist used geometry to displace, structure, and absorb his libidinal imagination. Rather than defining the painting as erotic, Moses made his painting practice synonymous with masculine, erotic energy while at the same time recognizing feminine erotic energy. As the layered compositions suggest, a painting is something (both space and object) to be entered as well as filled. Moreover, these two bodies of early work make it likely that on some level Moses associates geometry with landscape and gestural painting with the body.

Sorenson’s use of imbedded imagery within his grid structures – not to mention his insistence on including a signature zigzag in many of his 1980s figurative works – seems an attempt to bring together a variety of oppositional forces: abstraction and figuration, vectors and curves, flatness and depth, order and chaos.

Contemporary abstraction has largely devolved into lackadaisical amorphous blobs, concatenations of random spills, and flat fields of doodles. Rigor and intellect are today out of favor, subsumed by the glorification of the random and abject. Sorenson’s smart, rigorous abstract paintings rekindle an enterprise that can still stimulate the mind and fire the eye. Look at these paintings again!

Critic and independent curator Michael Duncan is a Corresponding Editor for Art in America. His writings have focused on underrated artists of the twentieth century, West Coast modernism, twentieth century figuration, and contemporary California art. His curatorial projects include surveys and recontextualizations of works by Pavel Tchelitchew, Sister Corita Kent, Kim MacConnel, Lorser Feitelson, Eugene Berman, Richard Pettibone, and Wallace Berman.

Melinda Wortz, “Introduction,” Don Sorenson: 1976-1978, exh. cat. (Los Angeles: Mount St. Mary’s College, 1978), p. 10.

Colin Gardner, “Don Sorenson,” Images & Issues, Vol. 4, No. 3, November/December 1983, p. 26.

Wortz, ibid.

John Yau, “The Depth and Surface of the Thing Itself as it Exists in the Passage of Time,” Ed Moses: A Retrospective of the Paintings and Drawings, 1951-1996, exh. cat. (Berkeley & Los Angeles: University of California Press, 1996), p. 19.