David Trulli

All Lines Are Busy

April 5 - 28, 2008

Gallery C2

Robert Berman Gallery presents a solo art exhibition from David Trulli titled “All Lines Are Busy,” a collection of new work that explores modern human networks and our ability to disconnect from them.

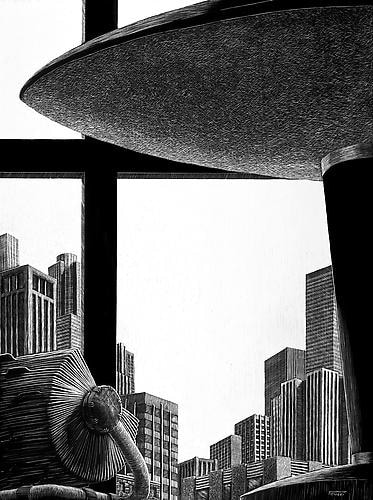

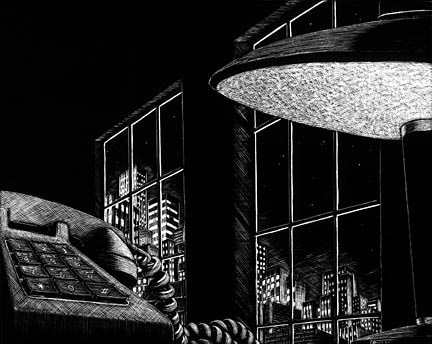

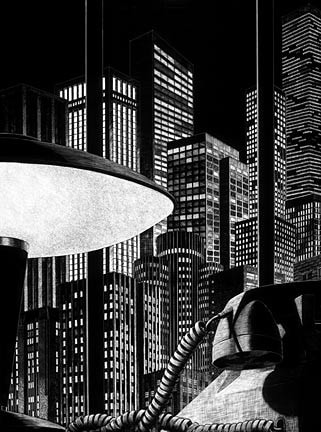

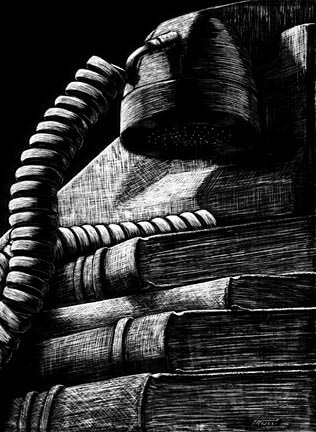

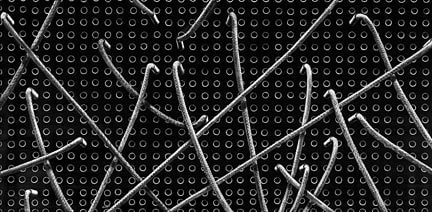

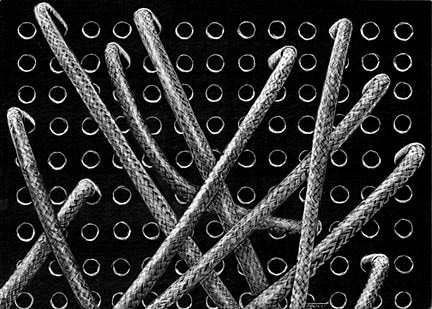

“Since the invention of the telephone we have become more and more inter-connected” says Trulli, “somehow, though, we still manage to find our own separate places, real or imagined.”David Trulli works in scratchboard: a white clay-coated board, covered with black ink. Fine knives are used to delicately scrape the ink away, creating the image.

A former cinematographer, Trulli compares working in scratchboard to lighting a film set: “it starts out black and you add light.” David Trulli was born in New York and came to Los Angeles in 1979.

He currently lives and works in Hollywood.

***

Whether by phone, computer or mere proximity, we are more interconnected than at any time in history. We exist in, and are surrounded by, invisible networks. Sooner or later, though, most of us would like to “disconnect” even if just for a little while.

It may not be possible to sever the links, but is it really necessary? There are so many connections, and with them so high a noise level, that maybe we can still find cover and comfort in spite of it all.

We are at once connected and disconnected, exposed and hidden. It is just one paradox of our modern lives.

-David Trulli

“All Lines Are Busy,” refers to the broadly understood irony of ubiquitous communication technology’s impact on society. We are both more connected and more isolated than ever, increasingly relying on mediated perceptions of the world as we voraciously devour information via the internet and cable news at the expense of real human contact. Trulli observes that “the people in most of the works seem to exist in a sort of fragile sanctuary; private places where the real world is very close at hand and always on the verge of intruding.” What is less immediately clear is whether they are in that limbo by choice, circumstance or the requirements of poetry.

It had been my intention to go into some detail about individual works in the series, but I changed my mind about that. There’s a real opportunity for individuals confronting Trulli’s work to locate themselves in his loose-weave narratives, and I think I’d be doing both the work and the audience a grave disservice were I to presume to direct that process. Whether the interplay between the regimented architectural testaments to man’s will that rivals the majesty of nature is romantic, utopian, nostalgic or tragic depends mainly on the predisposition of the viewer. It always does of course—Derrida has said that “we are all mediators, all translators”—but I think this is particularly salient in Trulli’s case.

Besides his open-mindedness he has a lot going for him. He has pitch-perfect but guileless draftsmanship, infinitive reserves of patience and discipline in his mark-making, and a classic, glamorous dexterity with the properties of light. He favors images in which lone figures consider their isolation in the world. He loves the grandeur and ambition of urban architecture and imbues every inch of it with meaning. His work can withstand art historical scrutiny but he takes a promethean pride in its accessibility to broad audiences. Fans of Mondrian’s electric rectangle boogies, Malevich’s plain, meditative flat shapes, Charles Burns’s melodramatic compositions and perspectives and Escher’s mathematical psychedelia will have just as many ways into the work as fans of Ed Wood’s iconoclastic humor and Fritz Lang’s industrial miasma. Everyone always wants to know how he does it, and the truth is there are major clues about the meaning of his art inherent in his technical choices, being the direct outgrowth of how he sees the world around him.

He fabricates his own scratchboards by laying white gesso down as the ground then covering it with black ink. He uses knives like pencils to scratch the black off in a reductive process that achieves the familiar goals of drawing by other means. It turns out Trulli worked for many years as a cinematographer, using a visual process that involved starting with a pitch-black room and adding light to create contours and depth. Most drawing adds shadow, Trulli found a way to draw by adding light. He coats the finished work with resin, to protect the surfaces but also to heighten contrasting tones in the spectacular sea of buildings, their regiments of windows, the orchestral advance and retreat of rooftops and towers. Life on film sets also taught him that what things look like is more important to the truth of a picture than how they actually are, so he thinks about what feels right, leaving room for chance and intuition in an unforgiving medium.

Excellence is not nearly as interesting to Trulli as authenticity, and in the end the harmonious dissonance of his images buzzes and hums like the city itself.

-Shana Nys Dambrot

Los Angeles 2008